Cost-Effective Analysis of Inflammatory Bowel Disease Models of Care, A Rural Perspective

Dr Thomas Skinner, BSci, M.D. [1,2,3] Dr Symret Singh, BCom M.D. [4, 5] , Dr Nishmi Gunasingam [1,3]

- Wagga Wagga Base Hospital, Murrumbidgee Local Health District, NSW

- St Vincent’s Hospital Sydney, NSW

- University of New South Wales, Faculty of Medicine, NSW

- Royal North Shore Hospital, Northern Sydney Local Health District, NSW

- University of Sydney, Faculty of Medicine and Health, NSW

Introduction

Unlike many chronic conditions, Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IBD) are often managed reactively, with escalation of patient care upon flares, either through emergency presentations or in the outpatient setting. IBD remains a significant healthcare burden with estimates of $100m directly attributable to hospital costs [2]. Alongside direct hospital costs, it’s estimated a further $361m productivity loss occurs from loss of earnings, premature death and absenteeism, with a further $2.7b of indirect costs to taxpayers from its morbidity [2]. A significant move has been made to standardise IBD models of care with the creation of the Inflammatory Bowel Disease National Action Plan [3], as informed through the national Inflammatory Bowel Disease Quality of Care Program Audit [4]. Accordingly, it is thought at least partial endorsement of the National Action Plan’s recommendations would lead to a reduced healthcare, personal and DALY-burden per capita. Translating these interventions to that which is appropriate, accessible and effective in outer regional, rural and remote settings presents challenges, and alternatives are discussed.

Aim

To demonstrate the healthcare burden of IBD, cost-effectiveness and feasibility of current best standard of care in IBD in outer regional, rural and remote settings.

Methods

IBD multidisciplinary models, national guidelines and recommendations were reviewed alongside audits of these interventions. Measures of disease burden were reviewed through national databases and statistics attained by the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW) alongside contributing factors to its change; population growth, population ageing and change in amount of disease/injury.

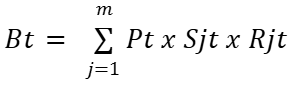

Bt is DALY, YLD

j age and sex group

m age and sex groups included (males and females aged 0 to 100+)

t is a time point

Pt is the total population size at time t

Sjt is the share of the population in age and sex group j at the time t

Rjt is the rate burden for disease/injury in the age and sex group j at the time t

Disability-Adjusted Life Years (DALY) = Years of Life Lost (YLL) + Years Lived with Disability (YLD)

Results

Nationally between 2003 and 2018, there was a 41% increase in IBD burden DALYs [1]. It is thought 28% of this can be attributed to population growth, 4% to population ageing and 9% due to the change in the amount of disease and injury. With regard to YLDs, the total non-fatal burden for all persons increased 56% over the same period [1]. 30% of this was attributed to population growth, 3% due to ageing and 23% due to the change in amount of disease/injury [1]. In 2018 it’s estimated this now makes up 22,755 YLDs with a total health loss of 24,110 DALYs [1].

Discussion

Upon national review in the 2016 audit of IBD services in Australia [4], The Inflammatory Bowel Disease National Action Plan in 2019 identified 8 priority areas [3]. One key observation and recommendation was made in response to the demonstrated 15-17% reduction in hospital admissions via Emergency Departments in health districts with an established, at least partial, IBD service: an IBD nurse >0.4 FTE, named clinical lead and IBD helpline [4]. Notably, in 2016 only 24% of sites had partial IBD services as per the definition above. The AIHW indicates the average length of stay for patients whom present with Crohn’s are 5.2 days, and 6.5 days of Crohn’s, which may infer significant savings pending partial IBD services successful roll out.

Key limitations to the provision of these partial IBD services in outer regional, rural and remote areas are many, and clear; the ability to attract and retain specialised IBD nurses is challenging and resource-intensive. In many areas, to attract a clinical lead can prove impossible on a longer-term basis. Of note, a study by Karimi et al. (2016) report success in implementing a nurse-led IBD advice-line and virtual clinic at Liverpool Hospital that manages 550 IBD patients during a 1-year period. The intervention answered 220 phone calls, 1017 virtual clinic consultations avoiding 53 GP visits, 159 IBD outpatient department visits, 6 emergency presentations and one hospital admission [5, 6]. This intervention cost an estimated $58,713, and thought to save $110,663 and proven clearly cost-effective [5, 6]. It is suggested a model similar to this, would work to not only complete the requirements to meet the threshold of a ‘partial IBD service’ but also help provide a service to bridge the geographical limitations to rural and remote services. In light of the many transferrable skillsets applicable to chronic disease management and assessment, an employed clinical nurse specialist may help assist with rheumatological, respiratory and other specialised chronic disease needs in their role.

Conclusion

The effective implementation of National IBD service recommendations may reduce costly reactive healthcare practices that lead to the propagation of burdensome outcomes to both the taxpayer, local health district and patients. In doing so, it is inferred a health district may be able to reduce inpatient admissions, Emergency Department presentations, and the other significant direct and indirect costs. Whilst there are distinct challenges in executing the recommendations in outer regional, rural and remote situational contexts, there have been successful hybrid tele-models that may help bridge these.

References

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW) 2021, Australian Burden of Disease Study 2018: Interactive data on disease burden. Available at: https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/burden-of-disease/abds-2018-interactive-data-disease-burden

- PricewaterhouseCoopers Australia (PwC). Improving inflammatory bowel disease care across Australia. March 2013. Available at: https://www.crohnsandcolitis.com.au/research/studies-reports/

- Department of Health and Aged Care 2019, National Strategic Action Plan for Inflammatory Bowel Disease, Australian Government, Canberra. Available at: https://www.health.gov.au/resources/publications/national-strategic-action-plan-for-inflammatory-bowel-disease

- Crohn’s & Colitis Australia (CCA) 2016, Final report of the first audit of the organisation and provision of IBD services in Australia 2016. Available at: https://crohnsandcolitis.org.au/advocacy/our-projects/ibd-audit-report/

- Karimi, N. , Sechi, A. , Harb, M. , Sawyer, E. , Williams, A. , Ng, W. & Connor, S. (2021). The effect of a nurse-led advice line and virtual clinic on inflammatory bowel disease service delivery: an Australian study. European Journal of Gastroenterology & Hepatology, 33 (1S), e771-e776. doi: 10.1097/MEG.0000000000002249.

- Burisch, J., Zhao, M., Odes, S., De Cruz, P., Vermeire, S., Bernstein, C. N., … Munkholm, P. (2023). The cost of inflammatory bowel disease in high-income settings: a Lancet Gastroenterology & Hepatology Commission. The Lancet. Gastroenterology & Hepatology, 8(5), 458–492. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2468-1253(23)00003-1